In a fantasy campaign there are usually magic items, from one-shot items like potions, to mighty relics forged by beings of incredible power, like Excalibur. Some fantasy gaming systems are quite explicit about where magic items come from, others are extremely vague. In this post we want to map out a space of possibilities, nothing more. There are two qualities we want to think about: the permanence of the item and the provenance of the item.

First, permanence

A potion is consumed, has an effect, and it is gone. In several of the campaigns that Dan and Andrew have played in over the years there are also single use items that are functionally similar to grenades, e.g. marble that emit a fireball when thrown and smashed into something hard. These are single use magic items. Next up the scale is charged items — like some wands — that have a fixed number of spells they can hold and you expend them like rounds from a gun. This subsets three ways. The least cool is a wand, a ring of wishes, or other charged item that cannot be recharged. In the middle are charged items that can be recharged with the additional issue of the difficulty of recharging them. The coolest version of a charged item is one that recharges itself, albeit slowly. This is a more plausible and continuous version of “three times per day” or similar constraints.

The next step up the ladder is permanent items, like a ring of invisibility or a magic sword. Once up and running these items function without running out or causing other problems. A permanent item may have an activation condition, from a secret word to needing to kill some dread monster. Some items are hard to turn off — like the cursed items in early D&D — which not only won’t turn off but get stuck on your finger. The nicest of these are things like rings that work when worn. There is a level above permanent: items that have a lasting effect even after you take them off. The fang of the great wolf not only turns you into a werewolf if it scratches you, it can do the same to others, and destroying it doesn’t help, except to stop the problem growing.

Next, Provenance

In the gaming system we use a player can make magic items that duplicate the effects of the spells he knows. The items can be charged, recharging, or permanent. The check on this is that in order to power an item the character must permanently sacrifice some of his spell points; these can be replenished by expending experience, but either way it is a real sacrifice. Spells that happen in a flash, like a fireball, cannot be made permanent. Making a permanent item extends the duration of the spell, that has a non-trivial duration, to “indefinite”. This system is not really balanced. Based on player behavior, magic items are too expensive if you have to sacrifice your personal mana points to make them. This means the rules for making magic items simply explain where a lot of the magic items come from.

As those of you that have read the post on moons know, there are far realms that are difficult to access and have their own types of magic. This gives us the next category of magic item: rare things from far away. The characters on the moon, that know magic, can make things the same way that the mages in the core area of the campaign can. The fact they know different magic means these things may be rare in the core area.

The next possibility is relics of a forgotten age. A lot of the items in the early forms of D&D were like this. The magic item exists, it has a lot of powers, and there is little or no clue as to how it was made. If the item really is a relic from an earlier era with a better understanding of magic, or simply more magic than exists in the present world, then the item is rare or even unique, but its a legitimate source of a magic item. It also permits the referee even better control over the supply of these items.

Another source of magic items is natural magic. The stormwood tree, for example, is from an area where there are huge thunderstorms all the time. It has not only a mystical immunity to lightning but the ability to store lighting as a source of energy. Arrows crafted from the wood of a stormwood tree can hold a charge that shorts out into the target, delivering a second dose of damage. The stormwood tree is just an example; the notion is to have magical things, wood, berries, metals like mithril, and mystic gems that exist in the world. These give another way to have a limiting resource on the supply of some types of magic and also can be the basis of quests.

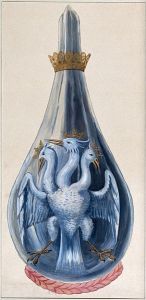

The last source of magic items is the powers, the gods, the primal forces, or whatever your campaign calls them. The sword Excalibur, forged when the world was young and man and beast and bird were one, is a unique magic item. A example on the dark side is the Wand of Orcus ™. These are unique items created by demigods or more powerful beings. These items should be used sparsely in a campaign and be woven into your underlying plot.

Mana stones and blood

Given that the rule requiring players to sacrifice their own spell points to make an item is too restrictive, we invented mana stones. These are mystical gems with mana in them. Carried by a mage they add their mana to his own. Left alone, they recharge independently at the same rate a mage does. Crafted into a magic item they can supply the mana that powers it. This permits the referee to hand out the potential to make magic items.

Originally, mana stones were white gems with a bit of mana in them. Useful general purpose magical treasure. Over time we realized that we could have different colors of mana stones. Green manastone, found in the roots of ancient trees that can only power nature spells. Black mana stones that are necromancy friendly and occasionally swipe a mana from their owner. Blue mana stones that have a strong disposition toward chaos. The full list of mana stones, their powers, mana levels, and where you find them is a subject for a future post. You can also make these up to suit your dramatic needs.

Another feature we added to ensure that there were magic items, more for the bad guys than the good guys, is to permit the creation of magic items with mana from a sacrifice. This usually means someone with mage potential, since you need enough mana, but we also included rare magical beasts that have lots of mana. Its important to emphasize to the player characters that human sacrifice is typically unacceptable — though in some very hard-core kingdoms execution for high crimes might include the penance of being used to power a magic item?

Final thoughts

Typically you need magic to be rare and somewhat risky to make an interesting campaign. A wizard that needs a cloak with ten wand loops is a bit excessive, besides a hobgoblin will probably kill him while he is dithering between the wand of fireballs and the wand of fishhooks. The source of magic items, the difficulty in getting the parts, and the difficulty in keeping items functioning all give you tools to keep your players at the sweet spot of access to magic items. As a last resort you can also give items their own minds and agendas. This is also a subject for a future post.

This is Dan of Dan and Andrew’s Game Place. Let me know what you think about this post in the comments. If you get ideas from this, give us a pointer!